Inside information from one of the world’s biggest sports betting companies reveals the secret techniques to stop punters winning.

Month: December 2019

With things like Monocle, Together and Indigenous, I’m thinking we can get there. There’s things I’d like to see that I’m working on bundling into my own take on a social reader (codename Brother Eye for now):

- I’d like to see from my reader who’ve interacted with a particular post. Bonus points if it’s sorted by people who I have marked a particular relationship with.

- The ability to surface recommendable content and also explain why it was shown without marketing jargon is also a big add.

- Having humane design principles built in is a must.

This is just a short list of things I’d want to see in said readers. I’ll add more as time goes on.

Unsurprisingly, strategy games tend to only engage with complexity when it can be converted into a military or economic trait, the rest is treated as irrelevant or merely aesthetic. The tendency, when looking at different populations, is to fixate on familiarities, either because something appears similar or because something supposedly essential is missing. Much of anthropology up until the midpoint of the last century could be crassly summarized in the question “how come all these people don’t have a State?”

In regards to publishing, I think that Verso Books has it right when they often offer substantial savings for eBooks as well as free eBooks for physical purchases. They also allow users full access to the text to load to whatever platform they choose.

This all reminds me of Craig Mod’s piece arguing that the .

It’s underwater—and the consequences are unimaginable.

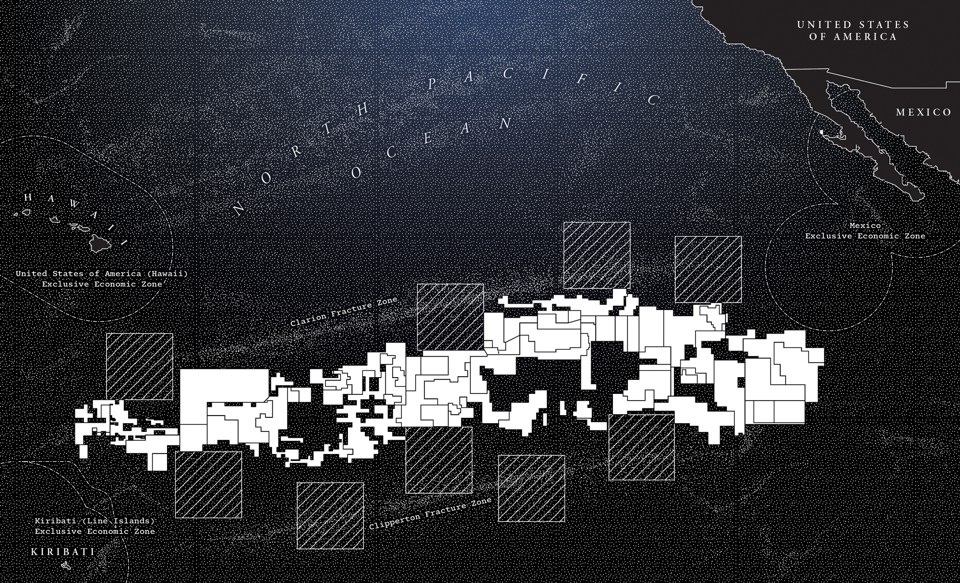

Deepwater plains are also home to the polymetallic nodules that explorers first discovered a century and a half ago. Mineral companies believe that nodules will be easier to mine than other seabed deposits. To remove the metal from a hydrothermal vent or an underwater mountain, they will have to shatter rock in a manner similar to land-based extraction. Nodules are isolated chunks of rocks on the seabed that typically range from the size of a golf ball to that of a grapefruit, so they can be lifted from the sediment with relative ease. Nodules also contain a distinct combination of minerals. While vents and ridges are flecked with precious metal, such as silver and gold, the primary metals in nodules are copper, manganese, nickel, and cobalt—crucial materials in modern batteries.

However, there are many concerned about environmental impact of such actions.

At full capacity, these companies expect to dredge thousands of square miles a year. Their collection vehicles will creep across the bottom in systematic rows, scraping through the top five inches of the ocean floor. Ships above will draw thousands of pounds of sediment through a hose to the surface, remove the metallic objects, known as polymetallic nodules, and then flush the rest back into the water. Some of that slurry will contain toxins such as mercury and lead, which could poison the surrounding ocean for hundreds of miles. The rest will drift in the current until it settles in nearby ecosystems. An early study by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences predicted that each mining ship will release about 2 million cubic feet of discharge every day, enough to fill a freight train that is 16 miles long. The authors called this “a conservative estimate,” since other projections had been three times as high. By any measure, they concluded, “a very large area will be blanketed by sediment to such an extent that many animals will not be able to cope with the impact and whole communities will be severely affected by the loss of individuals and species.”

One of the biggest issues is that there is so much of ocean that still remains unexplored and unknown. In particular, the hadel zone, the area of the ocean beyond 20,000 feet.

That environment is composed of 33 trenches and 13 shallower formations called troughs. Its total geographic area is about two-thirds the size of Australia. It is the least examined ecosystem of its size on Earth.

This is something Timothy Shank has spent his life working on.

Building a vehicle to function at 36,000 feet, under 2 million pounds of pressure per square foot, is a task of interstellar-type engineering. It’s a good deal more rigorous than, say, bolting together a rover to skitter across Mars. Picture the schematic of an iPhone case that can be smashed with a sledgehammer more or less constantly, from every angle at once, without a trace of damage, and you’re in the ballpark—or just consider the fact that more people have walked on the moon than have reached the bottom of the Mariana Trench, the deepest place on Earth.

One of the biggest problems is that the only people to have even entered the hadal zone are “the most committed multimillionaire, Hollywood celebrity, or special military program, and only in isolated dives to specific locations that reveal little about the rest of the hadal environment.”

Victor Vescoco, one of those multimillionaires, returned with news that rubbish had already beaten us to the bottom.

After his expedition to the trenches, Victor Vescovo returned with the news that garbage had beaten him there. He found a plastic bag at the bottom of one trench, a beverage can in another, and when he reached the deepest point in the Mariana, he watched an object with a large S on the side float past his window. Trash of all sorts is collecting in the hadal—Spam tins, Budweiser cans, rubber gloves, even a mannequin head.

In regards to other opportunities offered by the ocean, Craig Venter, a man who has made his money from genome research, has found a world of complex microbials.

Venter pointed out that ocean microbes produce radically different compounds from those on land. “There are more than a million microbes per milliliter of seawater,” he said, “so the chance of finding new antibiotics in the marine environment is high.” McCarthy agreed. “The next great drug may be hidden somewhere deep in the water,” he said. “We need to get to the deep-sea organisms, because they’re making compounds that we’ve never seen before. We may find drugs that could be used to treat gout, or rheumatoid arthritis, or all kinds of other conditions.”

In the end, with so much still unknown, the impact is impossible to truly measure

The harms of burning fossil fuels and the impact of land-based mining are beyond dispute, but the cost of plundering the ocean is impossible to know.

As a note, financial support for this extended piece was provided by the 11th Hour Project of the Schmidt Family Foundation.

For a different perspective on the ocean, check-out this infographic and web toy. Also, read Ben Taub’s feature on Victor Vescovo’s journey to become the first person to visit the deepest points in every ocean.

This reminds me from a few years ago and Tom Woodward’s attempt at a dashboard. I also wonder where data mirroring fits within Cory Doctorow’s discussions if adversarial interoperability. Although Kin Lane warns that interoperability is a myth.

Sadly, my current method is manual til it hurts. And it hurts.

This isn’t about shaming Instructure and it’s shareholders. This is about pointing out that we do not have any policies in place to prevent the exploitation of our schools and the students they serve. There is no approach to business or technology that will prevent the exploitation of student data. There is only a need to establish and strengthen federal and state policies that protect the privacy of students and their data, and minimizing the damage any platform can cause–no matter who owns it.

“If you are finding your students are being distracted on their cellphones or on laptops, you have to ask yourself: What am I doing in my teaching that is not engaging?” she said. “How can I give them opportunities to participate so they don’t feel the need to disappear down the rabbit hole?”

Australia’s Federal education ministers claim that Australia’s spending on education has never been higher and that expenditure has increased 25% or $10 billion since 2010. This ignores the fact that our student population has dramatically increased requiring spending on new schools, school infrastructures and of course more teachers. $8 billion of the extra funding (or 80 per cent) went to a mix of “everyday” items: rising student numbers, wage increases, and the ongoing costs of increased investments in government school buildings. Student numbers grew by 9 per cent, so the real increase per student was 14 per cent. Educating these extra students cost just under $4 billion, or two-fifths of the overall increase.

If you’ve wondered whether there were actually 30 people trying to book the same flight as you, you’re not alone. As Chris Baraniuk finds, the numbers may not be all they seem.

Do learners share information in ways that consider all sources?

Do learners consider the contributors and authenticity of all sources?

Do learners practice the safe and legal use of technology?

Do learners create products that are both informative and ethical?

Do learners avoid accessing another computer’s system, software, or data files without permission?

Do learners engage in discursive practices in online social systems with others without deliberately or inadvertently demeaning individuals and/or groups?

Do learners attend to the acceptable use policies of organizations and institutions?

Do learners attend to the terms of service and/or terms of use of digital software and tools?

Do learners read, review, and understand the terms of service/use that they agree to as they utilize these tools?

Do learners respect the intellectual property of others and only utilize materials they are licensed to access, remix, and/or share?

Do learners respect and follow the copyright information and appropriate licenses given to digital content as they work online?

What we learned from the spy in your pocket.

The data reviewed by Times Opinion didn’t come from a telecom or giant tech company, nor did it come from a governmental surveillance operation. It originated from a location data company, one of dozens quietly collecting precise movements using software slipped onto mobile phone apps. You’ve probably never heard of most of the companies — and yet to anyone who has access to this data, your life is an open book. They can see the places you go every moment of the day, whom you meet with or spend the night with, where you pray, whether you visit a methadone clinic, a psychiatrist’s office or a massage parlor.

This information is often used in cc combination with other data points to create a shadow profile.

As revealing as our searches of Washington were, we were relying on just one slice of data, sourced from one company, focused on one city, covering less than one year. Location data companies collect orders of magnitude more information every day than the totality of what Times Opinion received.

Until governments step in to curb such practices, we need to be a little more paranoid , as Kara Swisher suggests. While John Naughton wonders how the west is any different to China?

It throws an interesting light on western concerns about China. The main difference between there and the US, it seems, is that in China it’s the state that does the surveillance, whereas in the US it’s the corporate sector that conducts it – with the tacit connivance of a state that declines to control it. So maybe those of us in glass houses ought not to throw so many stones.

Another example such supports Naughton’s point is presented by the Washington Post which reported on how some colleges have taken to using smartphones to track student movements.

What I have noticed in 2019 from my perch of not-paying-full-attention would probably include these broad trends and narratives: the tangled business prospects of the ed-tech acronym market (the LMS, the OPM, the MOOC); the heightened (and inequitable) surveillance of students (and staff), increasingly justified as preventing school shootings; the fomentation of fears about the surveillance of Chinese tech companies and the Chinese government, rather than a recognition that American companies — and surely the US education system itself — has long perpetuated its own surveillance practices; and the last gasp of the (white, male) ed-tech/ed-reform evangelism, whose adherents seem quite angry that their bland hype machine is no longer uncritically lauded by a world that is becoming increasingly concerned about the biases and dangers of digital technologies.

Writing the Hack Education end-of-year series has always reminded me of how very short our memories seem to be. By December, we’ve forgotten what happened in January or June. And we’ve certainly forgotten what happened a year ago, two years ago, a decade ago. Or at least, that’s one way I can rationalize how someone like Chris Whittle can get such a glowing profile in The Washington Post this year for his latest entrepreneurial endeavor.

The answer: they didn’t! They reached their sweeping conclusions by analyzing YouTube *without logging in*, based on sidebar recommendations for a sample of channels (not even the user’s home page because, again, there’s no user). Whatever they measured, it’s not radicalization.

— Arvind Narayanan (@random_walker) December 29, 2019

He explains that we neither have the tools and vocabulary to make sense of such complexities.

In our data-driven world, the claim that we don’t have a good way to study something quantitatively may sound shocking. The reality even worse — in many cases we don’t even have the vocabulary to ask meaningful quantitative *questions* about complex socio-technical systems.

— Arvind Narayanan (@random_walker) December 29, 2019

The greatest challenge is the reality that YouTube and the algorithm are one and the same.

Consider the paper’s definition of radicalization: "YouTube’s algorithm [exposes users] to more extreme content than they would otherwise." Savvy readers are probably screaming: There is no "otherwise"! There is no YouTube without the algorithm! There is no neutral!

— Arvind Narayanan (@random_walker) December 29, 2019

On January 1, YouTube videos for kids will look much different. But will it be better?

Throughout its history, YouTube has stubbornly maintained that it’s a site aimed at users 13 and over, freeing the platform from obtaining parental consent to track user data. Yet the FTC’s investigation found that Google had been touting YouTube’s popularity with children to toy brands like Mattel and Hasbro in order to sell ads, including the assertion that YouTube is the No. 1 website regularly visited by kids.

The FTC’s fine is arguably a pittance of what Google owes. Though it may be a record-breaking fine for the organization, as Recode’s Peter Kafka explains, $170 million is basically “a rounding error” in YouTube’s profit, which could reach around $20 billion this year. Two of the FTC’s five commissioners voted against the settlement, with one arguing the fine should have been in the billions.

One of the biggest concerns is that much of this content is driven by algorithms, rather than the recommendations of educational specialists.

Maybe, though, the problem isn’t that the YouTube algorithm serves up stupid or bad videos to kids, but that an algorithm is in charge of what kids are watching at all. Toddlers are always going to click on the video with the brightest, most bonkers thumbnail with words they might recognize. Moving kids’ content to separate streaming apps — made specifically for children, with fewer commercials, more gatekeepers in charge of quality control, and fair, clear payment structures — seems like a change for good.

Alexis Madrigal (‘‘) and James Bridle (‘‘) also unpack some of the issues associated with YouTube.

Big Tech has given us a load of social platforms, and the content we’ve shared on those platforms has made them valuable. These platforms are designed to make it easy and convenient to share our thoughts and feelings. And they don’t cost us any money. The social nature of the platforms also make us feel validated. One button press for a like, a love, a star, a share, and we feel appreciated and connected. And it’s all for free. Except it isn’t.

Five historians wrote to us with their reservations. Our editor in chief replies.