I also really like your reimagining of the traditional linear table of contents. I wonder what implication that this might have for something like the IndieWeb, especially the organisation of the wiki. At the very least it might be useful for Greg McVerry and his investigation of the IndieWeb for education.

💬 Thesis Abstract

, I am excited to read both your findings, as well as your flânographic methodology. I am intrigued to what it might have in other areas beyond Twitter.

Ian, Aaron and couldn’t come at a better time. Working on this now: github.com/jgmac1106/blog… I need to keep writing and not get distracted thinking about how I can represent this study visually. Need to rewrite methods a bit ended up using something I have to call Participatory Narrative Analysis. quickthoughts.jgregorymcverry.com

I am really taken by the methodology (something that Deb Netolicky also used), especially as a means of capturing a glimpse of change and development over time. Thinking about those involved in the IndieWeb, everyone has a different story developed over time. Although it might be possible to write a vanilla on-boarding process, I wonder if it is ever so straightforward for anyone? For example, would this process be the same in a years time? What happens if you want to use Jekyl, rather than WordPress? Sometimes there is strength in ambiguity, maybe? Let me know if I can help with anything.

Also on:

Hi Aaron,

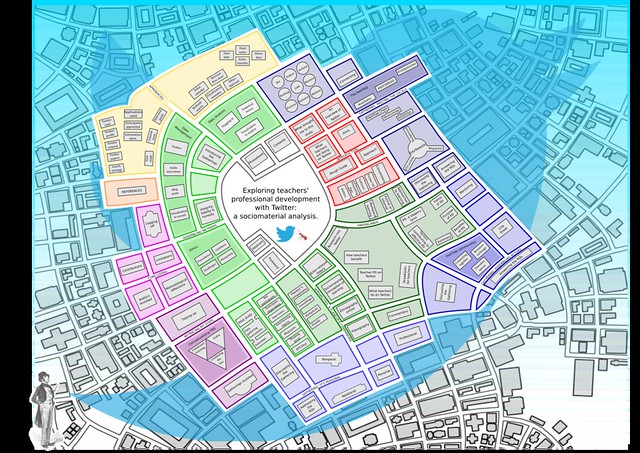

Thanks for taking a look and for the positive response. A linear, sequential table of contents did not seem at all in keeping with the spirit of the flâneur, a sensibility I tried to maintain throughout the study. Inspired by @debsnet (and with her permission), I developed flânography as a form of ethnography which maintained that spirit … more about that in a later post.

Although I can only claim to be on the periphery of the Indieweb (by association), thinking in terms of flânerie might have something to offer. It is about discovery through pathways of experience which are responsive, rather than being planned in advance. It’s about intermingled, interwoven individuality. [Writing that’s prompted a thought related to the Parkrun I did this morning. Let me just think that through …]

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MecAVFpd-kw?version=3&rel=1&fs=1&autohide=2&showsearch=0&showinfo=1&iv_load_policy=1&wmode=transparent&w=809&h=456%5D

Once more I am grateful to Aaron for taking the trouble to read and respond to one of my blog posts. In this case it was the preceding post where I launched my abstract and discussed the rationale behind rendering a visual ‘table of contents.’ In his response, Aaron mused whether flânographic methodology might provide a window on the Indieweb community and practice:

Just before replying to Aaron, I had received notification of the results from the Parkrun I did this morning. Whenever I run or cycle, I upload data from my Garmin to Strava and inevitably visit the site to update some of the details, such as the run type and name. Sometimes I’ll also use Strava’s ‘Flyby’ feature which presents animated markers on a map of your run, each marker representing other Strava members who passed by whilst you were recording. Reading Aaron’s observations, it struck me that a flyby shows ‘change over time’ and that different people have different stories.

I screencaptured a couple of flyby’s in the video which opens this post. The first segment shows a flyby for a Parkrun in which I participated (yes, I know I’m halfway down the field, but I am now in my sixties!). The second segment is a flyby from a recent bike ride in which I was cycling, ostensibly independently.

In the opening Parkrun segment, we all gathered at the same time in the same place, set off together around the same course, then finished at the same location. In the second segment, I set off from my starting place, but unbeknownst to me, many other people were active across similar terrain. Each departed independently from his or her own starting place, all at times of their choosing. They then carved out their own routes, although every so often our paths would cross or even become coincident, albeit at different times. Some travelled further, some faster; some stopped briefly, some travelled continuously. With no obligatory route, no stopwatch to beat, and unridden lanes beckoning enticingly, each participant was at liberty to conduct his or her own flânography. Look closely at the video segment and you’ll spot one interesting pair of cyclists who set off from different places, met at a location (near the centre of the map), then went off together.

I was struck by how the second video segment seemed similar to how Aaron described the Indieweb experience. Different people, different places, different times, different paths, but with regular points of intersection and coincidence. And sometimes clearly working together. This then prompted me to revisit the way that conventional PD might be distinguished from ‘Twitter PD,’as I referred to it. Certain forms of conventional PD are similar to the Parkrun flyby where there’s a pre-arranged ‘course’ to follow, people gather at an appointed time and all follow the same path. Some race through more quickly than others, but all are aiming for the same endpoint. What wasn’t apparent on the Parkrun flyby, but likely in conventional PD, were drop-outs – those who, for whatever reason, are unable to complete.

The cycling flyby seemed much more like Twitter PD, with people pursuing their own goals, each following their own path but occasionally intersecting, although often asynchronously. Even if within the same overall ‘space,’ independence, autonomy and personalisation are more significant here. There’s less formality, less structure and more serendipity. Of course as models, both flybys are somewhat limited, providing a sense of mobility, pathways and traversals, but not helpful if we need to think about interaction, exchange and relationships. We can’t see in the Parkrun flyby for example that I was desperately clinging to the coattails of someone I’d selected as a pacemaker.

I love Parkruns with other folks and I love running and cycling on my own; each has its own merits and issues. One of the strands which emerged in my study was that both planned, formal experiences and less formal, unstructured experiences each have their place. Some people might prefer one over the other, some find value in both. There are valid reasons why sometimes everyone needs to be following the same programme at the same time. However, teachers learning through Twitter clearly gain a great deal from being able to choose paths which address their individual needs and suit their contexts. Perhaps they are flâneurs/flâneuses? Perhaps we could be taking the best from both worlds?

Have now written a lengthier response, which I hope notified you through the webmention … if I posted it correctly!

cpdin140.wordpress.com/2018/11/11/pd-…