Deepwater plains are also home to the polymetallic nodules that explorers first discovered a century and a half ago. Mineral companies believe that nodules will be easier to mine than other seabed deposits. To remove the metal from a hydrothermal vent or an underwater mountain, they will have to shatter rock in a manner similar to land-based extraction. Nodules are isolated chunks of rocks on the seabed that typically range from the size of a golf ball to that of a grapefruit, so they can be lifted from the sediment with relative ease. Nodules also contain a distinct combination of minerals. While vents and ridges are flecked with precious metal, such as silver and gold, the primary metals in nodules are copper, manganese, nickel, and cobalt—crucial materials in modern batteries.

However, there are many concerned about environmental impact of such actions.

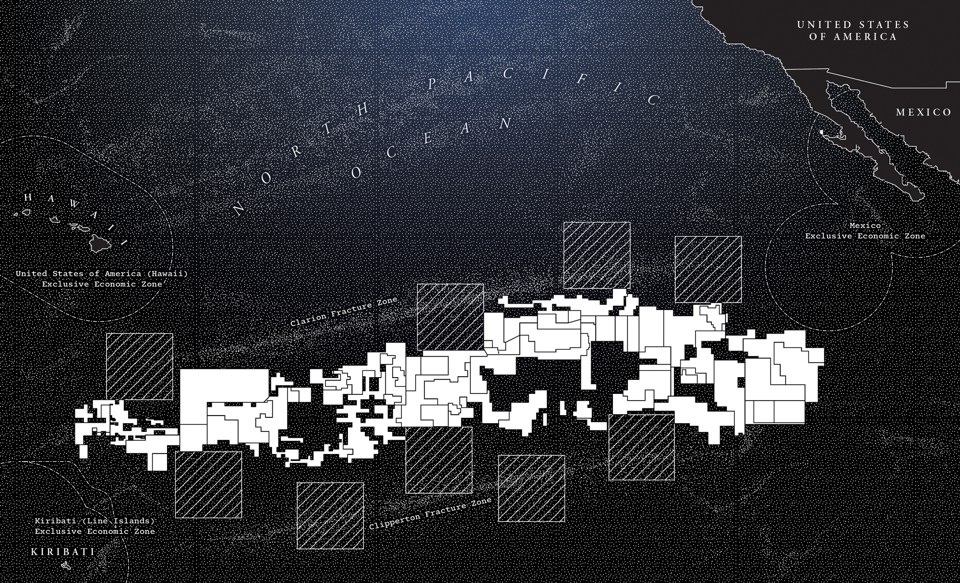

At full capacity, these companies expect to dredge thousands of square miles a year. Their collection vehicles will creep across the bottom in systematic rows, scraping through the top five inches of the ocean floor. Ships above will draw thousands of pounds of sediment through a hose to the surface, remove the metallic objects, known as polymetallic nodules, and then flush the rest back into the water. Some of that slurry will contain toxins such as mercury and lead, which could poison the surrounding ocean for hundreds of miles. The rest will drift in the current until it settles in nearby ecosystems. An early study by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences predicted that each mining ship will release about 2 million cubic feet of discharge every day, enough to fill a freight train that is 16 miles long. The authors called this “a conservative estimate,” since other projections had been three times as high. By any measure, they concluded, “a very large area will be blanketed by sediment to such an extent that many animals will not be able to cope with the impact and whole communities will be severely affected by the loss of individuals and species.”

One of the biggest issues is that there is so much of ocean that still remains unexplored and unknown. In particular, the hadel zone, the area of the ocean beyond 20,000 feet.

That environment is composed of 33 trenches and 13 shallower formations called troughs. Its total geographic area is about two-thirds the size of Australia. It is the least examined ecosystem of its size on Earth.

This is something Timothy Shank has spent his life working on.

Building a vehicle to function at 36,000 feet, under 2 million pounds of pressure per square foot, is a task of interstellar-type engineering. It’s a good deal more rigorous than, say, bolting together a rover to skitter across Mars. Picture the schematic of an iPhone case that can be smashed with a sledgehammer more or less constantly, from every angle at once, without a trace of damage, and you’re in the ballpark—or just consider the fact that more people have walked on the moon than have reached the bottom of the Mariana Trench, the deepest place on Earth.

One of the biggest problems is that the only people to have even entered the hadal zone are “the most committed multimillionaire, Hollywood celebrity, or special military program, and only in isolated dives to specific locations that reveal little about the rest of the hadal environment.”

Victor Vescoco, one of those multimillionaires, returned with news that rubbish had already beaten us to the bottom.

After his expedition to the trenches, Victor Vescovo returned with the news that garbage had beaten him there. He found a plastic bag at the bottom of one trench, a beverage can in another, and when he reached the deepest point in the Mariana, he watched an object with a large S on the side float past his window. Trash of all sorts is collecting in the hadal—Spam tins, Budweiser cans, rubber gloves, even a mannequin head.

In regards to other opportunities offered by the ocean, Craig Venter, a man who has made his money from genome research, has found a world of complex microbials.

Venter pointed out that ocean microbes produce radically different compounds from those on land. “There are more than a million microbes per milliliter of seawater,” he said, “so the chance of finding new antibiotics in the marine environment is high.” McCarthy agreed. “The next great drug may be hidden somewhere deep in the water,” he said. “We need to get to the deep-sea organisms, because they’re making compounds that we’ve never seen before. We may find drugs that could be used to treat gout, or rheumatoid arthritis, or all kinds of other conditions.”

In the end, with so much still unknown, the impact is impossible to truly measure

The harms of burning fossil fuels and the impact of land-based mining are beyond dispute, but the cost of plundering the ocean is impossible to know.

As a note, financial support for this extended piece was provided by the 11th Hour Project of the Schmidt Family Foundation.

For a different perspective on the ocean, check-out this infographic and web toy. Also, read Ben Taub’s feature on Victor Vescovo’s journey to become the first person to visit the deepest points in every ocean.